Pragmatic Unicode

Created 10 March 2012

This is a presentation I gave at PyCon 2012. You can read the slides and text on this page, or open the actual presentation in your browser, or watch the video:

Also, clicking the slide images will jump into the full presentation at that point. The Symbola font is included, but will have to be downloaded before some of the special symbols will appear.

Hi, I’m Ned Batchelder. I’ve been writing in Python for over ten years, which means at least a half-dozen times, I’ve made the same Unicode mistakes that everyone else has.

If you’re like most Python programmers, you’ve done it too: you’ve built a nice application, and everything seemed to be going fine. Then one day an accented character appeared out of nowhere, and your program started belching UnicodeErrors.

You kind of knew what to do with those, so you added an encode or a decode where the error was raised, but the UnicodeError happened somewhere else. You went to the new place, and added a decode, maybe an encode. After playing whack-a-mole like this for a while, the problem seemed to be fixed.

Then a few days later, another accent appeared in another place, and you had to play a little bit more whack-a-mole until the problem finally stopped.

So now you have a program that works, but you’re annoyed and uncomfortable, it took too long, you know it isn’t “right,” and you hate yourself. And the main thing you know about Unicode is that you don’t like Unicode.

You don’t want to know about weirdo character sets, you just want to be able to write a program that doesn’t make you feel bad.

You don’t have to play whack-a-mole. Unicode isn’t simple, but it isn’t difficult either. With knowledge and discipline, you can deal with Unicode easily and with grace.

I’ll teach you five Facts of Life, and give you three Pro Tips that will solve your Unicode problems. We’re going to cover the basics of Unicode, and how both Python 2 and Python 3 work. They are different, but the strategies you’ll use are basically the same.

The World & Unicode

We’ll start with the basics of Unicode.

The first Fact of Life: everything in a computer is bytes. Files on disk are a series of bytes, and network connections only transmit bytes. Almost without exception, all the data going into or out of any program you write, is bytes.

The problem with bytes is that by themselves they are meaningless, we need conventions to give them meaning.

To represent text, we’ve been using the ASCII code for nearly 50 years. Every byte is assigned one of 95 symbols. When I send you a byte 65, you know that I mean an upper-case A, but only because we’ve agreed beforehand on what each byte represents.

ISO Latin 1, or 8859-1, is ASCII extended with 96 more symbols.

Windows added 27 more symbols to produce CP1252. This is pretty much the best you can do to represent text as single bytes, because there’s not much room left to add more symbols.

With character sets like these, we can represent at most 256 characters. But Fact of Life #2 is that there are way more than 256 symbols in the world’s text. A single byte simply can’t represent text world-wide. During your darkest whack-a-mole moments, you may have wished that everyone spoke English, but it simply isn’t so. People need lots of symbols to communicate.

Fact of Life #1 and Fact of Life #2 together create a fundamental conflict between the structure of our computing devices, and the needs of the world’s people.

There have been a number of attempts to resolve this conflict. Single-byte character codes like ASCII map bytes to characters. Each one pretends that Fact of Life #2 doesn’t exist.

There are many single-byte codes, and they don’t solve the problem. Each is only good for representing one small slice of human language. They can’t solve the global text problem.

People tried creating double-byte character sets, but they were still fragmented, serving different subsets of people. There were multiple standards in place, and they still weren’t large enough to deal with all the symbols needed.

Unicode was designed to deal decisively with the issues with older character codes. Unicode assigns integers, known as code points, to characters. It has room for 1.1 million code points, and only 110,000 are already assigned, so there’s plenty of room for future growth.

Unicode’s goal is to have everything. It starts with ASCII, and includes thousands of symbols, including the famous Snowman, covers all the writing systems of the world, and is constantly being expanded. For example, the latest update gave us the symbol PILE OF POO.

Here is a string of six exotic Unicode characters. Unicode code points are written as 4-, 5-, or 6-digits of hex with a U+ prefix. Every character has an unambiguous full name which is always in uppercase ASCII.

This string is designed to look like the word “Python”, but doesn’t use any ASCII characters at all.

So Unicode makes room for all of the characters we could ever need, but we still have Fact of Life #1 to deal with: computers need bytes. We need a way to represent Unicode code points as bytes in order to store or transmit them.

The Unicode standard defines a number of ways to represent code points as bytes. These are called encodings.

UTF-8 is easily the most popular encoding for storage and transmission of Unicode. It uses a variable number of bytes for each code point. The higher the code point value, the more bytes it needs in UTF-8. ASCII characters are one byte each, using the same values as ASCII, so ASCII is a subset of UTF-8.

Here we show our exotic string as UTF-8. The ASCII characters H and i are single bytes, and other characters use two or three bytes depending on their code point value. Some Unicode code points require four bytes, but we aren’t using any of those here.

Python 2

OK, enough theory, let’s talk about Python 2. In the slides, Python 2 samples have a big 2 in the upper-right corner, Python 3 samples will have a big 3.

In Python 2, there are two different string data types. A plain-old string literal gives you a “str” object, which stores bytes. If you use a “u” prefix, you get a “unicode” object, which stores code points. In a unicode string literal, you can use backslash-u to insert any Unicode code point.

Notice that the word “string” is problematic. Both “str” and “unicode” are kinds of strings, and it’s tempting to call either or both of them “string,” but it’s better to use more specific terms to keep things straight.

Byte strings and unicode strings each have a method to convert it to the other type of string. Unicode strings have a .encode() method that produces bytes, and byte strings have a .decode() method that produces unicode. Each takes an argument, which is the name of the encoding to use for the operation.

We can define a Unicode string named my_unicode, and see that it has 9 characters. We can encode it to UTF-8 to create the my_utf8 byte string, which has 19 bytes. As you’d expect, reversing the operation by decoding the UTF-8 string produces the original Unicode string.

Unfortunately, encoding and decoding can produce errors if the data isn’t appropriate for the specified encoding. Here we try to encode our exotic Unicode string to ASCII. It fails because ASCII can only represent characters in the range 0 to 127, and our Unicode string has code points outside that range.

The UnicodeEncodeError that’s raised indicates the encoding being used, in the form of the “codec” (short for coder/decoder), and the actual position of the character that caused the problem.

Decoding can also produce errors. Here we try to decode our UTF-8 string as ASCII and get a UnicodeDecodeError because again, ASCII can only accept values up to 127, and our UTF-8 string has bytes outside that range.

Even UTF-8 can’t decode any sequence of bytes. Next we try to decode some random junk, and it also produces a UnicodeDecodeError. Actually, one of UTF-8’s advantages is that there are invalid sequences of bytes, which helps to build robust systems: mistakes in data won’t be accepted as if they were valid.

When encoding or decoding, you can specify what should happen when the codec can’t handle the data. An optional second argument to encode or decode specifies the policy. The default value is “strict”, which means raise an error, as we’ve seen.

A value of “replace” means, give me a standard replacement character. When encoding, the replacement character is a question mark, so any code point that can’t be encoded using the specified encoding will simply produce a “?”.

Other error handlers are more useful. “xmlcharrefreplace” produces an HTML/XML character entity reference, so that \u01B4 becomes “ƴ” (hex 01B4 is decimal 436.) This is very useful if you need to output unicode for an HTML file.

Notice that different error policies are used for different reasons. “Replace” is a defensive mechanism against data that cannot be interpreted, and loses information. “Xmlcharrefreplace” preserves all the original information, and is used when outputting data where XML escapes are acceptable.

You can also specify error handling when decoding. “Ignore” will drop bytes that can’t decode properly. “Replace” will insert a Unicode U+FFFD, “REPLACEMENT CHARACTER” for problem bytes. Notice that since the decoder can’t decode the data, it doesn’t know how many Unicode characters were intended. Decoding our UTF-8 bytes as ASCII produces 16 replacement characters, one for each byte that couldn’t be decoded, while those bytes were meant to only produce 6 Unicode characters.

Python 2 tries to be helpful when working with unicode and byte strings. If you try to perform a string operation that combines a unicode string with a byte string, Python 2 will automatically decode the byte string to produce a second unicode string, then will complete the operation with the two unicode strings.

For example, we try to concatenate a unicode “Hello ” with a byte string “world”. The result is a unicode “Hello world”. On our behalf, Python 2 is decoding the byte string “world” using the ASCII codec. The encoding used for these implicit decodings is the value of sys.getdefaultencoding().

The implicit encoding is ASCII because it’s the only safe guess: ASCII is so widely accepted, and is a subset of so many encodings, that it’s unlikely to produce false positives.

Of course, these implicit decodings are not immune to decoding errors. If you try to combine a byte string with a unicode string and the byte string can’t be decoded as ASCII, then the operation will raise a UnicodeDecodeError.

This is the source of those painful UnicodeErrors. Your code inadvertently mixes unicode strings and byte strings, and as long as the data is all ASCII, the implicit conversions silently succeed. Once a non-ASCII character finds its way into your program, an implicit decode will fail, causing a UnicodeDecodeError.

Python 2’s philosophy was that unicode strings and byte strings are confusing, and it tried to ease your burden by automatically converting between them, just as it does for ints and floats. But the conversion from int to float can’t fail, while byte string to unicode string can.

Python 2 silently glosses over byte to unicode conversions, making it much easier to write code that deals with ASCII. The price you pay is that it will fail with non-ASCII data.

There are lots of ways to combine two strings, and all of them will decode bytes to unicode, so you have to watch out for them.

Here we use an ASCII format string, with unicode data. The format string will be decoded to unicode, then the formatting performed, resulting in a unicode string.

Next we switch the two: A unicode format string and a byte string again combine to produce a unicode string, because the byte string data is decoded as ASCII.

Even just attempting to print a unicode string will cause an implicit encoding: output is always bytes, so the unicode string has to be encoded into bytes before it can be printed.

The next one is truly confusing: we ask to encode a byte string to UTF-8, and get an error about not being about to decode as ASCII! The problem here is that byte strings can’t be encoded: remember encode is how you turn unicode into bytes. So to perform the encoding you want, Python 2 needs a unicode string, which it tries to get by implicitly decoding your bytes as ASCII.

So you asked to encode to UTF-8, and you get an error about decoding ASCII. It pays to look carefully at the error, it has clues about what operation is being attempted, and how it failed.

Lastly, we encode an ASCII string to UTF-8, which is silly, encode should be used on unicode string. To make it work, Python performs the same implicit decode to get a unicode string we can encode, but since the string is ASCII, it succeeds, and then goes on to encode it as UTF-8, producing the original byte string, since ASCII is a subset of UTF-8.

This is the most important Fact of Life: bytes and unicode are both important, and you need to deal with both of them. You can’t pretend that everything is bytes, or everything is unicode. You need to use each for their purpose, and explicitly convert between them as needed.

Python 3

We’ve seen the source of Unicode pain in Python 2, now let’s take a look at Python 3. The biggest change from Python 2 to Python 3 is their treatment of Unicode.

Just as in Python 2, Python 3 has two string types, one for unicode and one for bytes, but they are named differently.

Now the “str” type that you get from a plain string literal stores unicode, and the “bytes” types stores bytes. You can create a bytes literal with a b prefix.

So “str” in Python 2 is now called “bytes,” and “unicode” in Python 2 is now called “str”. This makes more sense than the Python 2 names, since Unicode is how you want all text stored, and byte strings are only for when you are dealing with bytes.

The biggest change in the Unicode support in Python 3 is that there is no automatic decoding of byte strings. If you try to combine a byte string with a unicode string, you will get an error all the time, regardless of the data involved!

All of those operations I showed where Python 2 silently converted byte strings to unicode strings to complete an operation, every one of them is an error in Python 3.

In addition, Python 2 considers a unicode string and a byte string equal if they contain the same ASCII bytes, and Python 3 won’t. A consequence of this is that unicode dictionary keys can’t be found with byte strings, and vice-versa, as they can be in Python 2.

This drastically changes the nature of Unicode pain in Python 3. In Python 2, mixing unicode and bytes succeeds so long as you only use ASCII data. In Python 3, it fails immediately regardless of the data.

So Python 2’s pain is deferred: you think your program is correct, and find out later that it fails with exotic characters.

With Python 3, your code fails immediately, so even if you are only handling ASCII, you have to explicitly deal with the difference between bytes and unicode.

Python 3 is strict about the difference between bytes and unicode. You are forced to be clear in your code which you are dealing with. This has been controversial, and can cause you pain.

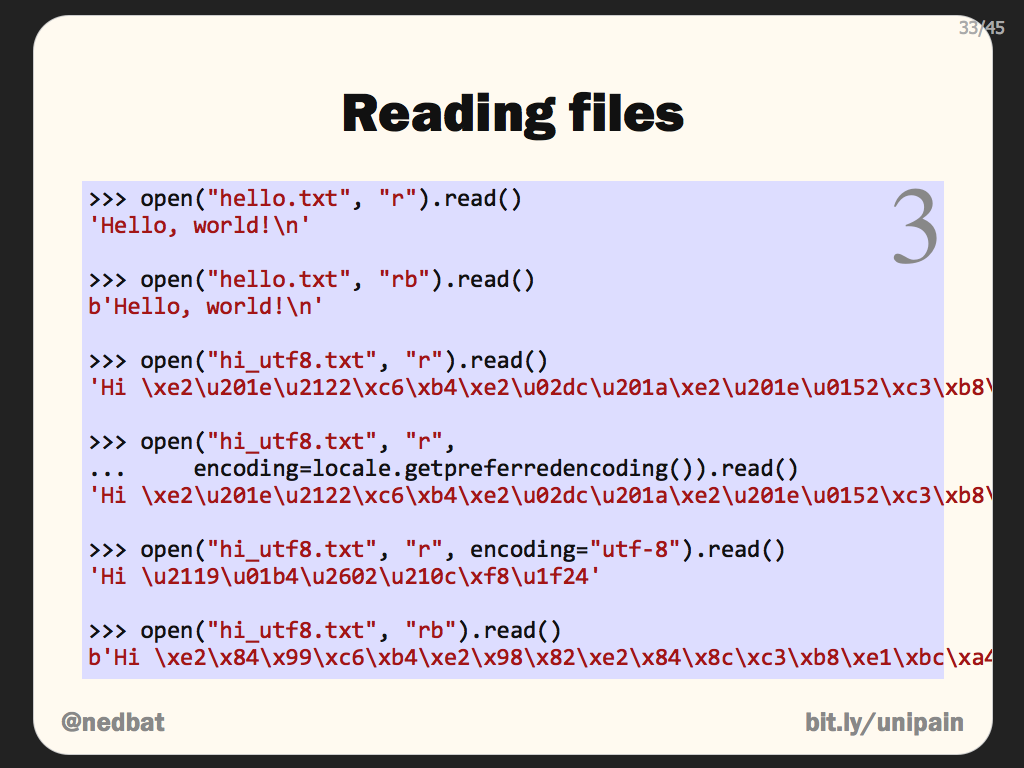

Because of this new strictness, Python 3 has changed how you read files. Python has always had two modes for reading files: binary and text. In Python 2, it only affected the line endings, and on Unix platforms, even that was a no-op.

In Python 3, the two modes produce different results. When you open a file in text mode, either with “r”, or by defaulting the mode entirely, the data read from the file is implicitly decoded into Unicode, and you get str objects.

If you open a file in binary mode, by supplying “rb” as the mode, then the data read from the file is bytes, with no processing done on them.

The implicit conversion from bytes to unicode uses the encoding returned from locale.getpreferredencoding(), and it may not give you the results you expect. For example, when we read hi_utf8.txt, it’s being decoded using the locale’s preferred encoding, which since I created these samples on Windows, is “cp1252”. Like ISO 8859-1, CP-1252 is a one-byte character code that will accept any byte value, so it will never raise a UnicodeDecodeError. That also means that it will happily decode data that isn’t actually CP-1252, and produce garbage.

To get the file read properly, you should specify an encoding to use. The open() function now has an optional encoding parameter.

Pain relief

OK, so how do we deal with all this pain? The good news is that the rules to remember are simple, and they’re the same for Python 2 and Python 3.

As we saw with Fact of Life #1, the data coming into and going out of your program must be bytes. But you don’t need to deal with bytes on the inside of your program. The best strategy is to decode incoming bytes as soon as possible, producing unicode. You use unicode throughout your program, and then when outputting data, encode it to bytes as late as possible.

This creates a Unicode sandwich: bytes on the outside, Unicode on the inside.

Keep in mind that sometimes, a library you’re using may do some of these conversions for you. The library may present you with Unicode input, or will accept Unicode for output, and the library will take care of the edge conversion to and from bytes. For example, Django provides Unicode, as does the json module.

The second rule is, you have to know what kind of data you are dealing with. At any point in your program, you need to know whether you have a byte string or a unicode string. This shouldn’t be a matter of guessing, it should be by design.

In addition, if you have a byte string, you should know what encoding it is if you ever intend to deal with it as text.

When debugging your code, you can’t simply print a value to see what it is. You need to look at the type, and you may need to look at the repr of the value in order to get to the bottom of what data you have.

I said you have to understand what encoding your byte strings are. Here’s Fact of Life #4: You can’t determine the encoding of a byte string by examining it. You need to know through other means. For example, many protocols include ways to specify the encoding. Here we have examples from HTTP, HTML, XML, and Python source files. You may also know the encoding by prior arrangement, for example, the spec for a data source may specify the encoding.

There are ways to guess at the encoding of the bytes, but they are just guesses. The only way to be sure of the encoding is to find it out some other way.

Here’s an example of our exotic Unicode string, encoded as UTF-8, and then mistakenly decoded in a variety of encodings. As you can see, decoding with an incorrect encoding might succeed, but produce the wrong characters. Your program can’t tell it’s decoding wrong, only when people try to read the text will you know something has gone wrong.

This is a good demonstration of Fact of Life #4: the same stream of bytes is decodable using a number of different encodings. The bytes themselves don’t indicate what encoding they use.

BTW, there’s a term for this garbage display, from the Japanese who have been dealing with this for years and years: Mojibake.

Unfortunately, because the encoding for bytes has to be communicated separately from the bytes themselves, sometimes the specified encoding is wrong. For example, you may pull an HTML page from a web server, and the HTTP header claims the page is 8859-1, but in fact, it is encoded with UTF-8.

In some cases, the encoding mismatch will succeed and cause mojibake. Other times, the encoding is invalid for the bytes, and will cause a UnicodeError of some sort.

It should go without saying: you should explicitly test your Unicode support. To do this, you need challenging Unicode data to pump through your code. If you are an English-only speaker, you may have a problem doing this, because lots of non-ASCII data is hard to read. Luckily, the variety of Unicode code points mean you can construct complex Unicode strings that are still readable by English speakers.

Here’s an example of overly-accented text, readable pseudo-ASCII text, and upside-down text. One good source of these sorts of strings are various web sites that offer strings like this for teenagers to paste into social networking sites.

Depending on your application, you may need to dig deeper into the other complexities in the Unicode world. There are many details that I haven’t covered here, and they can be very involved. I call this Fact of Life #5½ because you may not have to deal with any of this.

To review, these are the five unavoidable Facts of Life:

- All input and output of your program is bytes.

- The world needs more than 256 symbols to communicate text.

- Your program has to deal with both bytes and Unicode.

- A stream of bytes can’t tell you its encoding.

- Encoding specifications can be wrong.

These are the three Pro Tips to keep in mind as you build your software to keep your code Unicode-clean:

- Unicode sandwich: keep all text in your program as Unicode, and convert as close to the edges as possible.

- Know what your strings are: you should be able to explain which of your strings are Unicode, which are bytes, and for your byte strings, what encoding they use.

- Test your Unicode support. Use exotic strings throughout your test suites to be sure you’re covering all the cases.

If you follow these tips, you’ll write good solid code that deals well with Unicode, and won’t fall over no matter how wild the Unicode it encounters.

Other resources you might find helpful:

Joel Spolsky wrote The Absolute Minimum Every Software Developer Absolutely, Positively Must Know About Unicode and Character Sets (No Excuses!), which covers how Unicode works and why. It has no Python-specific information, but is better written than this talk!

If you need to deal with the semantics of arbitrary Unicode characters, the unicodedata module in the Python standard library has functions that can help.

For testing Unicode, the various “fancy” text generators for use on social networks work great.