Because of all that, when he does show us a genuine smile, it is like sunshine bursting through an overcast sky.

I took this picture nine years ago, but it’s still one of my favorites:

]]>If you look at the sidebar on the left, “More blog” lists tags and years interleaved in an unusual way: two tags, a year, a tag, a year. That pattern of five repeats:

python

coverage

‘25

my code

‘24

math

beginners

‘23

git

‘22

github

testing

‘21

audio

‘20

(etc)

I chose this pattern because it seemed to fill the space nicely and simpler schemes didn’t look as good. But how to implement it in a convenient way?

Generators are a good way to express iteration (a sequence of values) separately from the code that will consume the values. A simplified version of my sidebar code looks something like this:

def gen_sidebar_links():

# Get list of commonly used tags.

tags = iter(list_most_common_tags())

# Get all the years we've published.

years = iter(list_all_years())

while True:

yield next(tags)

yield next(tags)

yield next(years)

yield next(tags)

yield next(years)

This nicely expresses the “2/1/1/1 forever” idea, except it doesn’t work:

when we are done with the years, next(years) will raise a

StopIteration exception, and generators aren’t allowed to raise those so we have

to deal with it. And, I wanted to fill out the sidebar with some more tags once

the years were done, so it’s actually more like this:

def gen_sidebar_links():

# Get list of commonly used tags.

tags = iter(list_most_common_tags())

# Get all the years we've published.

years = iter(list_all_years())

try:

while True:

yield next(tags)

yield next(tags)

yield next(years)

yield next(tags)

yield next(years)

except StopIteration: # no more years

pass

# A few more tags:

for _ in range(8):

yield next(tags)

This relates to the original question because I only use this generator once to create a cached list of the sidebar links:

@functools.cache

def sidebar_links():

return list(gen_sidebar_links)

This is strange: a generator that’s only called once, and is used to make a list. I find the generator the best way to express the idea. Other ways to write the function feel more awkward to me. I could have built a list directly and the function would be more like:

def sidebar_links():

# ... Get the tags and years ...

links = []

try:

while True:

links.append(next(tags))

links.append(next(tags))

links.append(next(years))

links.append(next(tags))

links.append(next(years))

except StopIteration: # no more years

pass

for _ in range(8):

links.append(next(tags))

return links

Now the meat of the function is cluttered with “links.append”, obscuring the pattern, but could be OK. We could be tricky and make a short helper, but that might be too clever:

def sidebar_links():

# ... Get the tags and years ...

use = (links := []).append

try:

while True:

use(next(tags))

use(next(tags))

use(next(years))

use(next(tags))

use(next(years))

except StopIteration: # no more years

pass

for _ in range(8):

use(next(tags))

return links

Probably there’s a way to use the itertools treasure chest to create the interleaved sequence I want, but I haven’t tried too hard to figure it out.

I’m a fan of generators, so I still like the yield approach. I like that it focuses solely on what values should appear in what order without mixing in what to do with those values. Your taste may differ.

]]>Because of all that, when he does show us a genuine smile, it is like sunshine bursting through an overcast sky.

I took this picture nine years ago, but it’s still one of my favorites:

]]>I got a bunch of replies suggesting other ways. I wanted to post those, but I also wanted to check if they were right. A classic testing structure would have required putting them all in functions, etc, which I didn’t want to bother with.

So I cobbled together a test harness for them (also in a gist if you want):

GOOD = [

"",

"0",

"1",

"000000000000000000",

"111111111111111111",

"101000100011110101010000101010101001001010101",

]

BAD = [

"x",

"nedbat",

"x000000000000000000000000000000000000",

"111111111111111111111111111111111111x",

"".join(chr(i) for i in range(10000)),

]

TESTS = """

# The original checks

all(c in "01" for c in s)

set(s).issubset({"0", "1"})

set(s) <= {"0", "1"}

re.fullmatch(r"[01]*", s)

s.strip("01") == ""

not s.strip("01")

# Using min/max

"0" <= min(s or "0") <= max(s or "1") <= "1"

not s or (min(s) in "01" and max(s) in "01")

((ss := sorted(s or "0")) and ss[0] in "01" and ss[-1] in "01")

# Using counting

s.count("0") + s.count("1") == len(s)

(not (ctr := Counter(s)) or (ctr["0"] + ctr["1"] == len(s)))

# Using numeric tests

all(97*c - c*c > 2351 for c in s.encode())

max((abs(ord(c) - 48.5) for c in "0"+s)) < 1

all(map(lambda x: (ord(x) ^ 48) < 2, s))

# Removing all the 0 and 1

re.sub(r"[01]", "", s) == ""

len((s).translate(str.maketrans("", "", "01"))) == 0

len((s).replace("0", "").replace("1", "")) == 0

"".join(("1".join((s).split("0"))).split("1")) == ""

# A few more for good measure

set(s + "01") == set("01")

not (set(s) - set("01"))

not any(filter(lambda x: x not in {"0", "1"}, s))

all(map(lambda x: x in "01", s))

"""

import re

from collections import Counter

from inspect import cleandoc

g = {

"re": re,

"Counter": Counter,

}

for test in cleandoc(TESTS).splitlines():

test = test.partition("#")[0]

if not test:

continue

for ss, expected in [(GOOD, True), (BAD, False)]:

for s in ss:

result = eval(test, {"s": s} | g)

if bool(result) != expected:

print("OOPS:")

print(f" {s = }")

print(f" {test}")

print(f" {expected = }")

It’s a good thing I did this because a few of the suggestions needed adjusting, especially for dealing with the empty string. But now they all work, and are checked!

BTW, if you prefer Mastodon to BlueSky, the posts are there too: first and second.

Also BTW: Brian Okken adapted these tests to pytest, showing some interesting pytest techniques.

]]>Nat loves his routines, and wants to know what is going to happen. We make him a two-week calendar every weekend, laying out what to expect coming up. Thanksgiving was tricky this year for a few reasons. First, it was especially late in the year. In the early weeks of November, he looked at his calendar and said, “Thursday.” We figured out that he meant, “it’s November, so there should be a special Thursday, but I don’t see it here.” I added on an extra row so he could see when Thanksgiving was going to happen.

But there were other complications. After a few rounds of planning, we ended up with two Thanksgivings: the first on Thursday with my sister, which we’ve hardly ever done, and then a second on Friday with Susan’s family, the usual cohort. We’d be staying in a hotel Thursday night.

We tried to carefully keep Nat informed about the plan and talked about it a number of times. He was great with all of it, all the way through the Friday meal. But driving home Friday night, he seemed a little bothered. We asked him, “what’s wrong?” A common answer to that is “no,” either because he’s not sure how to explain, or he’s not sure he’s allowed to question what’s happening, or some other form of passivity. It’s hard to get an answer because if you offer options (“do your feet hurt?”) he might just repeat that even if it isn’t the real problem.

I thought maybe he was concerned about what was going to be happening next, and often going over the routine helps. So we started to review the plan. I asked, “where are we sleeping tonight?” He answered “Brookline.”

“Tomorrow where will you eat breakfast?” — “Brookline.”

“Where will you eat lunch?” — “Brookline.”

“Where will you eat dinner?” — Here we expected he’d name his group home, but instead he said — “dinner.”

Aha! This was the clue we needed. Here’s another tricky thing about Thanksgiving: if you have a meal at 4pm (as we had on Thursday), that counts as dinner. But what if you have a meal at 2pm as we had on Friday? Even if it’s a large meal and you aren’t hungry, by the time it gets dark shouldn’t there be dinner? We didn’t have dinner! This was what was bothering him. We had completely skipped over part of the expected routine. And even with all our planning, we hadn’t thought to explain that Grandma’s big Friday meal was going to be both lunch and dinner.

So we asked, “Do you want to stop somewhere to have dinner?” — “Yes.” So we stopped at McDonald’s for a crispy chicken sandwich (removed from the bun, dipped in sweet & sour sauce), fries and a Sprite. Judging from the noises once we were back in the car, maybe he was stuffing himself on principle, but we were back on the routine, so everyone was happy.

It’s not easy to find out what Nat wants, so when he tells us, even indirectly, we try to give it to him. Some people might have resisted making a stop when we were already late getting home, or having a meal when no one was actually hungry. But it wasn’t difficult and didn’t take long. It was a small thing to do, but felt like a large part of parenting: listening to your children’s needs no matter how quiet, and helping to meet them even when they are different than your own.

]]>Hubert Humphrey laid out a rubric I think we are doing poorly at:

The ultimate moral test of any government is the way it treats three groups of its citizens. First, those in the dawn of life — our children. Second, those in the shadows of life — our needy, our sick, our handicapped. Third, those in the twilight of life — our elderly.

Trump’s second term is a huge concern to me. He will cause chaos and turmoil. He will change institutions for the worse. Expertise will be mocked and science will be ignored. Too many people emboldened by his ascendance will give in to their worst impulses.

But I remain optimistic about the future. We will heal and restore. I don’t know how long it will take, but we will. Martin Luther King Jr said:

We shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.

I am proud to be an American and I love what America can be at its best. There is too much ugliness in American discourse and behavior today, but America is more than that. I am proud to fly the flag.

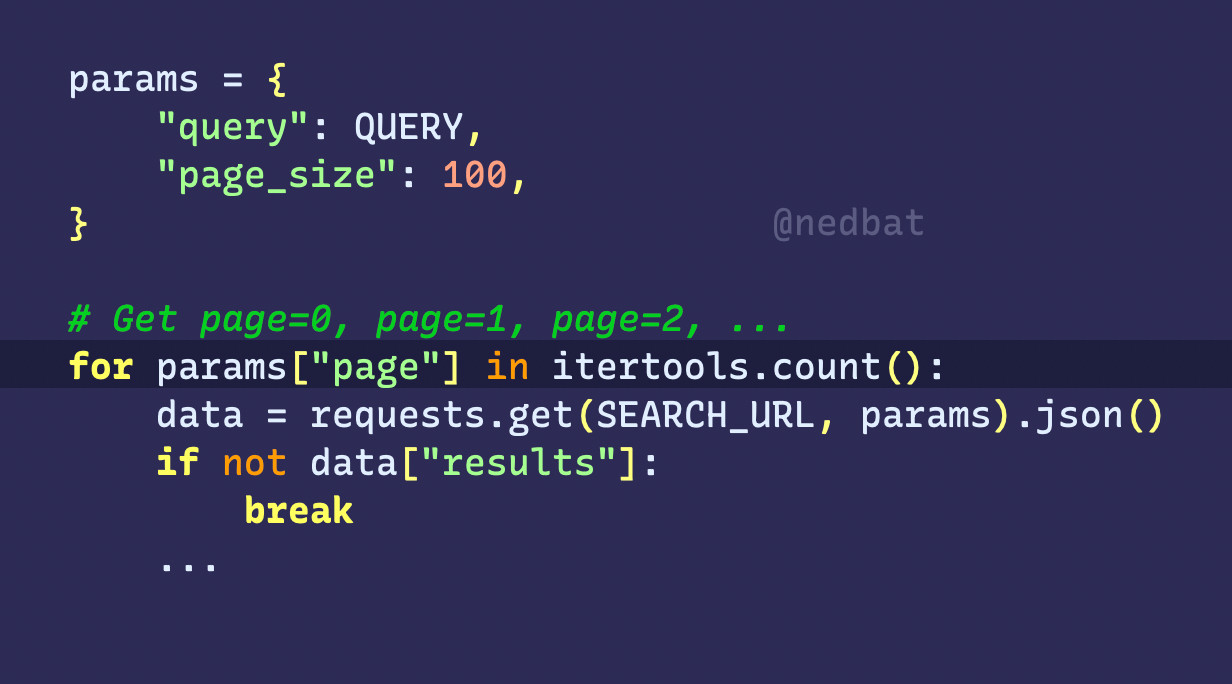

params = {

"query": QUERY,

"page_size": 100,

}

# Get page=0, page=1, page=2, ...

for params["page"] in itertools.count():

data = requests.get(SEARCH_URL, params).json()

if not data["results"]:

break

...

This code makes successive GET requests to a URL, with a params dict as the data payload. Each request uses the same data, except the “page” item is 0, then 1, 2, and so on. It has the same effect as if we had written it:

for page_num in itertools.count():

params["page"] = page_num

data = requests.get(SEARCH_URL, params).json()

One reply asked if there was a new params dict in each iteration. No, loops in Python do not create a scope, and never make new variables. The loop target is assigned to exactly as if it were an assignment statement.

As a Python Discord helper once described it,

While loops are “if” on repeat. For loops are assignment on repeat.

A loop like for <ANYTHING> in <ITER>: will take successive

values from <ITER> and do an assignment exactly as this statement

would: <ANYTHING> = <VAL>. If the assignment statement is

ok, then the for loop is ok.

We’re used to seeing for loops that do more than a simple assignment:

for i, thing in enumerate(things):

...

for x, y, z in zip(xs, ys, zs):

...

These work because Python can assign to a number of variables at once:

i, thing = 0, "hello"

x, y, z = 1, 2, 3

Assigning to a dict key (or an attribute, or a property setter, and so on) in a for loop is an example of Python having a few independent mechanisms that combine in uniform ways. We aren’t used to seeing exotic combinations, but you can reason through how they would behave, and you would be right.

You can assign to a dict key in an assignment statement, so you can assign to it in a for loop. You might decide it’s too unusual to use, but it is possible and it works.

]]>I already had a copy of Gareth’s original page about coverage.py, which now links to my local copy of coverage.py from 2001. BTW: that page is itself a historical artifact now, with the header from this site as it looked when I first copied the page.

The original coverage.py was a single file, so the “coverage.py” name was literal: it was the name of the file. It only had about 350 lines of code, including a few to deal with pre-2.0 Python! Some of those lines remain nearly unchanged to this day, but most of it has been heavily refactored and extended.

Coverage.py now has about 20k lines of Python in about 100 files. The project now has twice the amount of C code as the original file had Python. I guess in almost 20 years a lot can happen!

It’s interesting to see this code again, and to reflect on how far it’s come.

]]>Action workflows can be esoteric, and continuous integration is not everyone’s top concern, so it’s easy for them to have subtle flaws. A tool like zizmor is great for drawing attention to them.

When I ran it, I had a few issues to fix:

But- name: "Summarize"

run: |

echo "### From branch ${{ github.ref }}" >> $GITHUB_STEP_SUMMARY

github.ref is a branch name chosen by the author of the pull request.

It could have a shell injection which could let an attacker exfiltrate secrets.

Instead, put the value into an environment variable, then use it to interpolate:

- name: "Summarize"

env:

REF: ${{ github.ref }}

run: |

echo "### From branch ${REF}" >> $GITHUB_STEP_SUMMARY

- name: "Check out the repo"

uses: actions/checkout@11bd71901bbe5b1630ceea73d27597364c9af683 # v4.2.2

with:

persist-credentials: false

- name: "Push digests to pages"

env:

GITHUB_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.token }}

run: |

git config user.name nedbat

git config user.email ned@nedbatchelder.com

git remote set-url origin https://x-access-token:${GITHUB_TOKEN}@github.com/${GITHUB_REPOSITORY}.git

There were some other things that were easy to fix, and of course, you might have other issues. One improvement to zizmor: it could link to explanations of how to fix the problems it finds, but it wasn’t hard to find resources, like GitHub’s Security hardening for GitHub Actions.

William Woodruff is zizmor’s author. He was incredibly responsive when I had problems or questions about using zizmor. If you hit a snag, write an issue. It will be a good experience.

If you are like me, you have repos lying around that you don’t think about much. These are a special concern, because their actions could be years old, and not well maintained. These dusty corners could be a good vector for an attack. So I wanted to check all of my repos.

With Claude’s help I wrote a shell script to find all git repos I own and run zizmor on them. It checks the owner of the repo because my drive is littered with git repos I have no control over:

#!/bin/bash

# zizmor-repos.sh

echo "Looking for workflows in repos owned by: $*"

# Find all git repositories in current directory and subdirectories

find . \

-type d \( \

-name "Library" \

-o -name "node_modules" \

-o -name "venv" \

-o -name ".venv" \

-o -name "__pycache__" \

\) -prune \

-o -type d -name ".git" -print 2>/dev/null \

| while read gitdir; do

# Get the repository directory (parent of .git)

repo_dir="$(dirname "$gitdir")"

# Check if .github/workflows exists

if [ -d "${repo_dir}/.github/workflows" ]; then

# Get the GitHub remote URL

remote_url=$(git -C "$repo_dir" remote get-url origin)

# Check if it's our repository

# Handle both HTTPS and SSH URL formats

for owner in $*; do

if echo "$remote_url" | grep -q "github.com[/:]$owner/"; then

echo ""

echo "Found workflows in $owner repository: $repo_dir"

~/.cargo/bin/zizmor "$repo_dir/.github/workflows"

fi

done

fi

done

After fixing issues, it’s very satisfying to see:

% zizmor-repos.sh nedbat BostonPython

Looking for workflows in repos owned by: nedbat BostonPython

Found workflows in nedbat repository: ./web/stellated

🌈 completed ping-nedbat.yml

No findings to report. Good job!

Found workflows in nedbat repository: ./web/nedbat_nedbat

🌈 completed build.yml

No findings to report. Good job!

Found workflows in nedbat repository: ./scriv

🌈 completed tests.yml

No findings to report. Good job!

Found workflows in nedbat repository: ./lab/gh-action-tests

🌈 completed matrix-play.yml

No findings to report. Good job!

Found workflows in nedbat repository: ./aptus/trunk

🌈 completed kit.yml

No findings to report. Good job!

Found workflows in nedbat repository: ./cog

🌈 completed ci.yml

No findings to report. Good job!

Found workflows in nedbat repository: ./dinghy/nedbat

🌈 completed test.yml

🌈 completed daily-digest.yml

🌈 completed docs.yml

No findings to report. Good job!

Found workflows in nedbat repository: ./dinghy/sample

🌈 completed daily-digest.yml

No findings to report. Good job!

Found workflows in nedbat repository: ./coverage/badge-samples

🌈 completed samples.yml

No findings to report. Good job!

Found workflows in nedbat repository: ./coverage/django_coverage_plugin

🌈 completed tests.yml

No findings to report. Good job!

Found workflows in nedbat repository: ./coverage/trunk

🌈 completed dependency-review.yml

🌈 completed publish.yml

🌈 completed codeql-analysis.yml

🌈 completed quality.yml

🌈 completed kit.yml

🌈 completed python-nightly.yml

🌈 completed coverage.yml

🌈 completed testsuite.yml

No findings to report. Good job!

Found workflows in BostonPython repository: ./bospy/about

🌈 completed past-events.yml

No findings to report. Good job!

Nice.

]]>First, some basic aliases for operations I do often:

[alias]

br = branch

co = checkout

sw = switch

d = diff

di = diff

s = status -s -b --show-stash

These are simple, but others could use some explanation.

I have a few aliases for committing code. The “ci” alias provides the default option “--edit” so that even if I provide a message on the command line with “git ci -m”, it will pop me into the editor to provide more detail. “git amend” is for updating the last commit with the latest file edits I’ve made, and “git edit” is for updating the commit message on the latest commit:

[alias]

ci = commit --edit

amend = commit --amend --no-edit

edit = commit --amend --only

I work in many repos. Many have a primary branch called “main” but in some it’s called “master”. I don’t want to have to remember which is which, so I have an alias “git ma” that returns me to the primary branch however it’s named. It uses a helper alias to find the name of the primary branch:

[alias]

# Find the name of the primary branch, either "main" or "master".

primary = "!f() { \

git branch -a | \

sed -n -E -e '/remotes.origin.ma(in|ster)$/s@remotes/origin/@@p'; \

}; f"

If you haven’t seen this style of alias before, the initial exclamation point

means it’s a shell command not a git command. Then we use shell

f() {···}; f syntax to define a function and immediately invoke

it. This lets us use shell commands in a pipeline, access arguments with

$1, and so on. (Fetching GitHub pull requests has

more about this technique.)

This alias uses the “git branch -a” command to list all the branches, then pipes it into the Unix sed command to find the remote one named either “main” or “master”.

With “git primary” defined, we can define the “ma” alias to switch to the primary branch and pull the latest code. I like “ma” because it’s short for both main and master, and because it feels like coming home (“Hi ma!”):

[alias]

# Switch to main or master, whichever exists, and update it.

ma = "!f() { \

git checkout $(git primary) && \

git pull; \

}; f"

For repos with an upstream, I need to pull their latest code and also push to my fork to get everything in sync. For that I have “git mma” (like ma but more):

[alias]

# Pull the upstream main/master branch and update our fork.

mma = "!f() { \

git ma && \

git pull upstream $(git primary) --ff-only && \

git push; \

}; f"

For personal projects, I don’t use pull requests to make changes. I work on a branch and then merge it to main. The “brmerge” alias merges a branch and then deletes the merged branch:

[alias]

# Merge a branch, and delete it here and on the origin.

brmerge = "!f() { \

: git show; \

git merge $1 && \

git branch -d $1 && \

git push origin --delete $1; \

}; f"

This shows another technique: the : git show; command does

nothing but instructs zsh’s tab completion that this command takes the same

arguments as “git show”. In other words, the name of a branch. That argument

is available as $1 so we can use it in the aliased shell commands.

Often what I want to do is switch from my branch to main, then merge the branch. The “brmerge-” alias does that. The “-” is similar to “git switch -” which switches to the branch you last left:

[alias]

# Merge the branch we just switched from.

brmerge- = "!f() { \

git brmerge $(git rev-parse --abbrev-ref @{-1}); \

}; f"

Finally, “git brdone” is what I use from a branch that has already been merged in a pull request. I return to the main branch, and delete the work branch:

[alias]

# I'm done with this merged branch, ready to switch back to another one.

brdone = "!f() { \

: git show; \

local brname=\"$(git symbolic-ref --short HEAD)\" && \

local primary=\"$(git primary)\" && \

git checkout ${1:-$primary} && \

git pull && \

git branch -d $brname && \

git push origin --delete $brname; \

}; f"

This one is a monster, and uses “local” to define shell variables I can use in a few places.

There are other aliases in my git config file, some of which I’d even forgotten I had. Maybe you’ll find other useful pieces there.

]]>